The nation's high school graduation rate is at an all-time high, but high-poverty schools face a stubborn challenge. Schools in Miami and Pasadena are trying to do things differently.

September 1, 2016

At Booker T. Washington Senior High School in Miami, the doors open as early as 5 a.m. Many students come early and stay late because they have no place else to go, the principal and teachers say.

"Half the time the kids come to school just to eat," said Diane Burgess, who works at Booker T. "Just to be able to have light (and) running water."

Booker T. is in a neighborhood called Overtown. It's less than two miles from the restaurants, hotels and luxury condos of downtown Miami. But it's a long two miles. Nearly a third of families in Overtown (ZIP code: 33136) live on less than $15,000 a year, and nine out of every 10 students at the school come from low-income families.

Booker T. is what's known as a high-poverty school. That means more than 75 percent of the students are eligible for free or reduced price meals. There's been a big rise in the percentage of high-poverty schools in America. One in four public schools in America is a high-poverty school, double what it was back in the late 1990s.

Graduation rates by race and income

Going to a school where nearly all of your classmates are poor puts you at a huge disadvantage educationally and, particularly when it comes to the most basic educational outcome — getting a high school diploma. Kids from middle and upper income families have a 9 in 10 chance of graduating from high school on time. But a quarter of kids from low-income families don't finish high school.

This story examines what kids in poverty are up against when it comes to getting through high school, and how two public schools, Booker T. in Miami and a charter school in California, are trying to help more of them graduate. It takes more than focusing on grades or test scores. Kids in poverty need help with such basic needs as food and housing.

The ABCs at Booker T.

If you want to find the students most likely to drop out of high school, the place to look is Algebra 1. More students fail Algebra 1 than any other class.

In a ninth-grade algebra class at Booker T., an eager bunch of students clearly understood equations the teacher was writing on the white board. But there was also a bunch of kids who looked confused, distracted, even a little angry.

After the teacher-led lesson, those students met with a tutor at the back of the classroom to get some extra help. The tutoring is part of an experiment at Booker T. to try to prevent students from quitting high school. The experiment, called Diplomas Now and led by Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, is based on research that shows you can predict with a remarkable degree of accuracy who will drop out of high school by looking at three things. Researchers call them the ABCs.

Absences. Behavior. Course performance.

A ninth-grader who comes to school less than 90 percent of the time, has two or more behavior infractions, such as a suspension, and has a failing grade in math or English has a less than 25 percent chance of graduating from high school. The experiment underway at Booker T. is to take all that predictive data, put it together, and see if it can actually prevent a kid from quitting school.

How much does a high school diploma pay?

Researchers built something called the Early Warning Indicator system to collect all the data about a student's absences, behavior and course performance in one place. Some students stand out immediately.

At a weekly meeting of teachers and staff, Maria Stauble, an employee of Johns Hopkins who is based at Booker T. as part of Diplomas Now, was talking about one such student named Daniela (not her real name).

"The first thing that stands out to me is that her grades have significantly dropped from having straight Cs last year," Stauble told the group. The girl was failing algebra, science and English, and she was skipping school a lot.

"She started off the first nine weeks — I wouldn't say strong, but decent," said her English teacher, Elizabeth Briano. "There was at least effort there."

But now it was the middle of the school year and when Daniela did come to class, she mostly just sat there, doing nothing. She didn't even bring a backpack.

"She just sounds so uninterested in school," said another staff member. "That's what she told me. She's like, I don't want to be here, I don't want to do anything, I don't, just, like, nothing. Arms crossed."

Someone else said Daniela covers her mouth a lot, as though she might have some kind of dental problem. Another said Daniela's clothes were often stained and a bit smelly. "I think that there's something going on at home," Briano said. "Or something not going on at home, coupled with just a general lack of caring. That's what I've observed."

So, what can they do for Daniela? There aren't obvious answers. They have other students with big problems, too. One missed a couple months of school because he apparently hit his mom — or maybe stabbed her — and was locked up or in some kind of rehab. Another is a 17-year-old ninth-grader.

Just because schools can identify who's at risk of dropping out, doesn't mean they can figure out what to do about it. What the teachers and staff at Booker T. come up with is tutoring for one student, special education testing for another and a home visit for Daniela, the girl with dirty clothes and no backpack.

Help with everything from umbrellas to tampons

Supplying some of the firepower behind this individualized attention is an organization called City Year. It's a bit like a domestic Peace Corps, getting recent college graduates to spend a year in a high-poverty school working as tutors and mentors. There are eight of them at Booker T. as part of Diplomas Now. They do the tutoring in algebra, as well as in ninth-grade English. And after school, the City Year team gathers in a classroom to call the parents of the ninth-graders who didn't show up that day.

Absenteeism is a big issue at Booker T. and other high-poverty schools across the country. One study found that up to a third of students in high-poverty urban areas miss a month or more of school per year. On a typical day at Booker T., as many as one in five students are absent for all or part of the day.

The City Year team at Booker T. tried to reach parents to find out why their children were absent, but they didn't actually reach many of them. Instead, they got a lot of messages that phone numbers had been disconnected. They had more luck getting through at the beginning of the school year, said City Year volunteer Kayla Nicholson. "You know, at this point in the year people's numbers have changed."

That's a sign of poverty. Middle-class parents will have the same phone number for years, but when you're struggling to put food on the table, often the phone bill doesn't get paid.

When team members did get through, they often reached someone other than a parent.

In one case it was a guy who ran a group home. In another it was an aunt who said her nephew missed school because of the rain.

The rain?

It's an excuse Robert Balfanz, the researcher at Johns Hopkins who helped design Diplomas Now, has heard before. He said, on the one hand, it sounds pretty lame.

"On the other hand," he said, "many kids don't have rain gear. They don't have umbrellas. If it's pouring out, it means they will be torrentially soaked.

"One of the greatest acts of grace I have ever seen in my life was at an inner-city bus stop, it's torrential rain, there are kids there after school waiting for their bus, thoroughly soaked to the bone. Somebody pulls up, opens up the back of their trunk, hands them an umbrella, and drives off."

Balfanz said dropping out of high school is typically the result of many things that add up — little things like not having rain gear and big things like failing algebra. Almost every kid, rich or poor, runs into some kind of problem along their way in school. But when something goes wrong for a student in a middle- or upper-income home, their families can typically help.

"If a kid is struggling, they can get them a psychologist, they can get them a tutor," Balfanz said. "In high-poverty environments, if a school doesn't provide them, they don't get provided."

A key element in dropout prevention at Booker T. falls to Karla Mena. She works for Communities In Schools, one of the partners in the Diplomas Now project. Mena's job is to help students with the things going on in their lives outside of school that can make doing well in school difficult. She can hook students up with things such as bus passes, housing assistance, therapists and food. One day last winter, she met with a 12th-grader named Stephany Lopez, one of Mena's regulars.

Lopez's family was homeless, living in a motel. Her mom had mental health issues. Her stepdad could be violent. Lopez wanted to get away, go live with a family friend, but she was worried about her mother. "I don't know what can happen when I am gone," Lopez told Ms. Mena.

Lopez was also worried about her little sister. Lopez was making sure she got to school every day. But despite all the stuff going on in her life, Lopez was doing really well in school. Her grades were As and Bs, no Ds or Fs. What are some of the specific ways Mena helped her?

"She was there to help me when I was very hungry," Lopez said. "She was able to feed me." Mena even supplied tampons when Lopez needed them, drawing on a supply of every-day stuff in her office — school supplies, back packs, shampoo, sunglasses, all things that kids in poverty may not be able to afford.

Lopez's plan is to go to college and become an occupational therapist. She's one of the kids the Diplomas Now program seems to have helped. But it's not helping everyone.

VOICES

Listen to students talk about why they don't like the word "dropout."

At the end of the school year, among Mena's duties was to pay a home visit to Daniela, the ninth-grader with dirty clothes and no backpack.

Mena took a security guard along. "We knew the apartment complex, we didn't know the apartment," said Mena. They asked the neighbors, who pointed to an apartment that looked abandoned. "We knocked and there was no one there," said Mena.

But then they noticed an extension cord running power into the apartment through a window.

"The window was half open and I was able to look in and there was a lot of aluminum foil everywhere." She wasn't quite sure what to make of that, but aluminum foil is commonly used to do drugs.

Mena wasn't able to find Daniela or her family that day. Back at school, Mena tried to get Daniela to open up to her, but Daniela was really closed off and resistant. At that point, with just a few weeks left in the school year, Daniela had an F in every single class.

"She checked out, basically," Mena said. "I have not seen her."

Once a thriving neighborhood

The percentage of students at Booker T. who live in low-income families has increased over the past 15 years. That's been true for all of Miami and Florida as a whole.

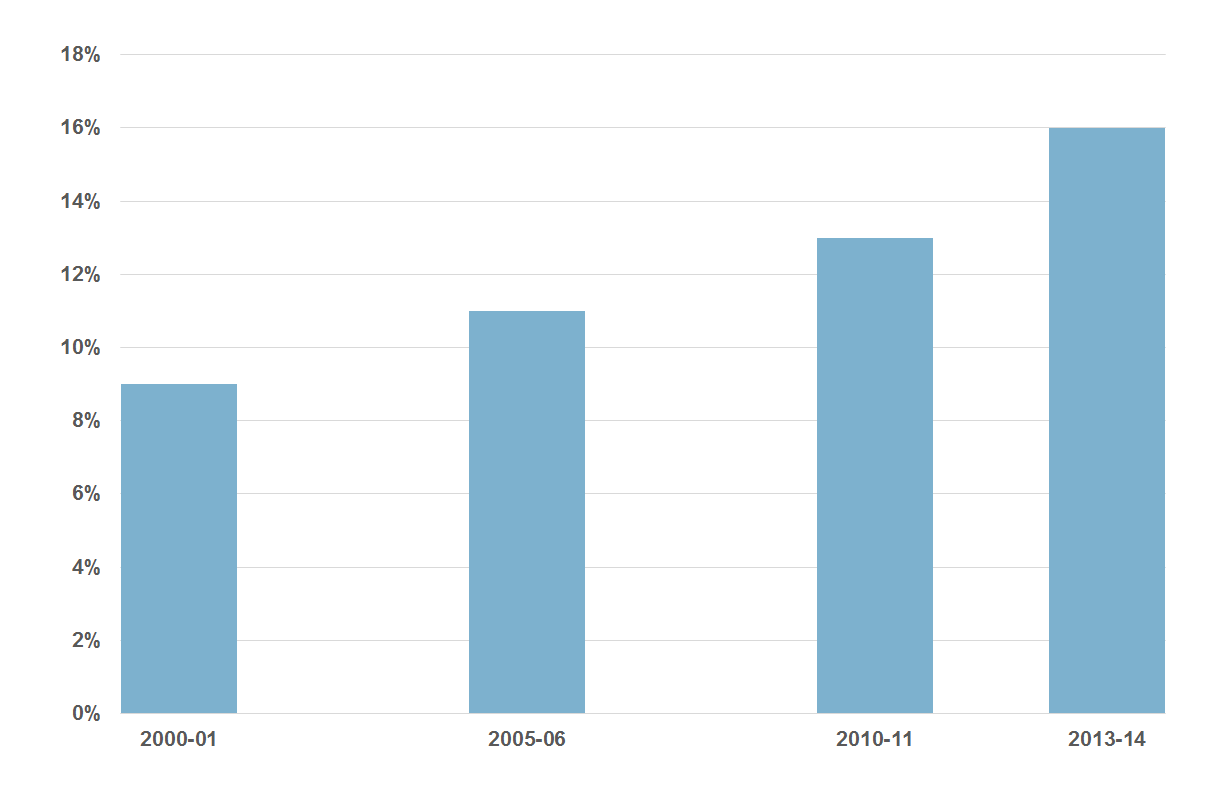

Rising poverty among students in public schools

To get a sense of what living conditions are like for many Booker T. students, the principal, William Aristide, arranges for new teachers to get a tour of the neighborhood.

What they see in Overtown are housing projects, vacant lots, and corner stores that advertise free ice when you buy liquor. Under the Interstate 95 bridge that cuts through the middle of the neighborhood, there are homeless people and drug addicts living in tents and sleeping on the sidewalks. Frequently, small memorials with candles, teddy bears and flowers pop up, to remember people who have been shot and killed.

But the neighborhood wasn't always like this. Overtown was once a thriving place, known as the Harlem of the South because of the many famous black musicians who performed there, and stayed in the neighborhood's hotels when segregation prevented them from staying in other parts of Miami.

"About this time of day we would see Ella Fitzgerald, Bojangles, Smokey Robinson," said Dr. Dorothy Jenkins Fields, sitting in the lobby of the historic Lyric Theater on a hot spring afternoon. Fields is an archivist and historian who grew up in Overtown and helped save the Lyric Theater from demolition.

"You'd see them walking around, going to the restaurants, and there were restaurants here," said Fields, pointing toward the streets of Overtown. "And not fast food restaurants. These were linen table cloths and napkins and all of that."

Fields graduated from Booker T. in 1960. She said the famous performers would often visit the school, and give performances. Nat King Cole gave piano lessons, she said with a delighted giggle.

It's hard to overestimate how important Booker T. was to this community. When it was built in 1926, it was the first public high school for black students in all of south Florida (at the time there were as many as 425 counties in the Southern United States where there was not a single public high school for black students). Kids came from all over to go to Booker T. One teacher said his great grandfather, who was apparently a rum runner, brought his granddaughters by boat from Key West every week so they could go to high school.

VOICES

Listen to Pinkney and Morton sing the Booker T. alma mater.

"It was expected that we would achieve academic excellence here," said Agnes Morton, a graduate of the class of 1955.

"People think that because we went to school during the days of segregation that we had an inferior education," said Enid Pinkney, class of 1949. "But it has not turned out that way for me."

It's clear from talking to alums that Booker T. provided what they considered a great education, prepared many of them for college, and put them on a path to middle-class lives. But by the early 2000s, education researchers had labelled Booker T. a "dropout factory." In 2003, the graduation rate was just 27 percent.

How did things get so bad at Booker T.? A lot of it has to do with how the neighborhood changed, and those changes began with the construction of Interstate 95.

I-95 was hailed by many people as a great moment of urban renewal. But for people in Overtown, urban renewal was just another name for white people wiping out a black neighborhood.

"It destroyed the community," said Fields. "It literally destroyed the community."

To make way for I-95, thousands of homes and businesses in Overtown were demolished. Silent film footage from 1966 shows the mayor of Miami-Dade County operating the wrecking ball that destroys a building, while dozens of black children watch from a nearby balcony.

Another thing that happened in the 1960s? Desegregation. That meant the middle class in Overtown could leave, and they did. Desegregation also meant that some black students in Overtown got bused to other Miami schools. But white students apparently never got bused in. Hispanic students started coming, but true racial integration never came to Booker T. What the school got out of the whole deal was economic isolation: a school full of kids from poor families.

The growth of high-poverty schools

The graduation rate at Booker T. Washington Senior High School had climbed to 74 percent by 2015.

The increase over that time reflects a rise in graduation rates across the country, beginning when the federal No Child Left Behind Act, in 2002, required states to improve their high school graduation rates. Before that law, there wasn't even a standard way to measure graduation rates.

Once it became clear just how bad things were at some high schools, states and districts put more money and staffing power into many of those schools to try to turn things around. The Miami-Dade School district, for example, created an Education Transformation Office to serve Booker T. and 18 other persistently low-achieving schools.

The number of high schools in the United States considered "dropout factories" has also decreased. Back in the early 2000s, when Booker T. earned that notorious label, there were about 2,000 high schools in the United States where at least 4 in 10 students were not making it to graduation. Those 2,000 schools — 18 percent of all high schools in the U.S. at the time — were producing more than half of the nation's dropouts. Nearly half of all African American high school students in the country, and nearly 40 percent of Hispanic high school students, went to one of these schools.

The latest data show the number of dropout factories has been cut in half, and those 1,000 schools now account for about 30 percent of all high school dropouts in the United States.

Progress is being made, and Booker T. is one of the schools making progress.

Booker T. catches up

But still, a stubborn and large contingent of students is not getting through. Black students graduate 10 percentage points behind the national average; Hispanic students graduate 6 points behind.

The problem, in large part, is high-poverty high schools like Booker T. Almost every dropout factory high school, current and former, is a high-poverty school. Nearly half of all black and Hispanic students in the United States go to a high-poverty school. In contrast, only 8 percent of white students are in schools where the vast majority of their classmates are low income.

This systemic isolation of students by race and family income is a huge obstacle when it comes to closing educational achievement gaps. Research shows the percentage of a student's schoolmates who are poor is a strong predictor of academic achievement, even after accounting for a child's own family income and socioeconomic status.

America once tried to close achievement gaps by de-segregating public schools, but the country has largely turned its back on de-segregation. Public schools in the United States are more racially segregated now than they were in the 1970s, and the percentage of schools where the vast majority of students are black or Hispanic and poor has nearly doubled in the past 15 years.

Changes in the percentage of high-poverty schools comprised of mostly black or Hispanic students

That means schools like Booker T. need to come up with programs that help students overcome the effects of poverty. That's what Diplomas Now was designed to do.

It's not yet clear how much of an impact the program had. There were 62 schools across the country involved in the experiment, all high-poverty schools like Booker T. Half of them got the Diplomas Now program. Half of them didn't. Researchers are still collecting and analyzing data so there are a lot of unanswered questions.

But some early results show that Diplomas Now had a statistically significant impact on the number of students in a school who ended up having none of those early warning indicators that predicted they would drop out. In other words, students in the Diplomas Now schools were less likely to get off track when it came to their absences, their behavior and their course performance. Something about Diplomas Now seemed to prevent students from becoming at-risk for not finishing high school. But the Diplomas Now program, according to the data so far, did not have an impact on the students who came into high school already in trouble. In other words, if a student started high school already behind academically, already with a history of chronic absenteeism, already with behavior issues — the Diplomas Now program didn't seem to help them get back on track.

That's the problem a public charter school in southern California is trying to tackle.

Chasing students, literally, in Pasadena

Dominick Correy is a chaser. That's his job title at Learning Works, a school aimed at helping students who didn't make it in traditional high schools.

Starting early, Correy hits the streets in a purple car known as a chaser mobile. He drives all over the Los Angeles area to pick up students and bring them to school. On the back of the chaser mobile in big white letters it says, "High School Dropout?" and provides the school phone number.

First up on a November day in 2015 was a student named Brian. "Twenty years old and tattoos on his head and stuff like that," Correy said. "But he lives in his enemy territory so he doesn't catch the bus because he could get killed catching the bus trying to come to school."

Next was Mario. "He hasn't been here in maybe like three weeks," said Correy. "He'll come in regularly, then fall off the face of the earth and come back in. Last year with Mario I had leverage because he was on probation."

Coming to school was a condition of Mario's probation, but now that he's off, Correy said it's hard to motivate him to come to school.

Then Kenneth. He was supposed to be waiting outside his house, but he wasn't so Correy called. A woman answered and when Correy told her he was here to take Kenneth to school, she sounded thrilled, and sent him out. Kenneth is 18. Until two weeks earlier, he hadn't been in school for two years.

If Kenneth tried to go to a traditional high school, he'd be at least 21 by the time he could graduate. And frankly, a traditional high school doesn't want a student like Kenneth because there's too much of a chance he'd enroll and then quit, raising the school's dropout rate. But Learning Works is all about students like Kenneth.

"We take take everybody," said Correy. "We're going to do whatever it's going to take to get them to graduate. Whatever it's going to take."

Learning Works was started 10 years ago by Mikala Rahn, an education researcher who has done large-scale evaluations for the California Department of Education.

"We've created a system for masses and we don't know what to do with the fringes," Rahn said.

Like at Booker T., virtually all of the students at Learning Works are people of color from low-income families.

About 400 students are enrolled at the school, including students at a second Learning Works location in the Boyle Heights neighborhood of Los Angeles. On any given day, about a third of the students show up.

Students work at their own pace, making their way through "modules." Each module is akin to a credit. For each module, the students might do some reading, some work in a textbook, and attend a certain number of classes. There might also be a science lab or a field trip. There are lots of field trips at Learning Works, to the theater, museums, the zoo — places kids in poverty almost never go. Then at the end of each module, students do some kind of project.

Each teacher has about 30 assigned students and works with them one-on-one in whatever subjects the student needs to be able to graduate. Each teacher also has a chaser. The chasers are all former high school dropouts.

"They understand us, and they believe in us," said student Bethany Martinez. "And people like us, the kids here, we need that. We don't have really anything. When we're on the streets, it's just us. But when we're here, it's all of us."

'Regular schools don't do 24/7'

Martinez's chaser is Roberto Guerra, a Learning Works graduate. "When I was in regular school, I never met my counselor," he said. "No one ever asked how my day was going, no one asked if I was hungry or if my home situation was OK. No one asked. No one cared. And here it's not like that. When you walk in, everyone is saying hi. Everyone is asking questions."Guerra chases for teacher Ruth Richardson. "Each student that comes in, we're going to find a way to love 'em," Richardson said. "And these students were not loved anywhere else."

Students at Learning Works spend most of their time in what's known as the warehouse. It's a big open space with tables where students work one-on-one with their teachers. There are things here you'd find at any school: a periodic table on the wall, a screen that announces upcoming events like Taco Friday and cupcake grams for Valentine's day.

But this place is unlike a traditional school in almost every other way. For example, rules that exist in regular schools were being broken by the minute here: students were texting, listening to music, coming and going, eating, napping, swearing. Swearing is technically forbidden. "I think we have a swear jar over on Chelsea's desk," said Richardson, pointing to another teacher's desk. "It doesn't rake in a lot of cash," she said with a laugh.

No one is worried about enforcing rules for rules' sake here. The point is to help students do what they need to do to get a high school diploma.

"If they don't show up for three weeks, we can still put an intense week in and get them caught up," Richardson said.

Learning Works exists by virtue of a provision in California law that allows students to do something called independent study. That provision was designed, not for the students who are here, but for actors, actresses, people in the hospital or others whose schedules or life circumstances make traditional school impossible.

Learning Works was founded on the notion that for kids in poverty, traditional school is often impossible, too.

Viridiana Mendez is an example. She worked full-time at a restaurant and her schedule changed a lot, so she couldn't be at school every day from 8 until 3. But she couldn't quit her job because, at 19, she was supporting herself and helping to pay for her parents' immigration lawyer. They were trying to come back to the United States from Mexico, where they had returned when Mendez was 14, leaving her with her older siblings. "It's hard," Mendez said, "to grow up without someone being there with you."

Edward Lugo, 19, is another. He'd been at Learning Works for almost five years. He lived with his great grandmother, who couldn't provide much more than a place to stay. "I earn everything I get on my own," he said. "Like, no one buys me my laundry soap, no one does my laundry. No one, you know? I have to support myself in every single way."

And so does Ana Luquin, 18. Her mother left her when she was a baby. She'd been in foster homes, the juvenile justice system and, she estimated, as many as 30 different schools.

This spring, she was one credit from graduating and hoping to go to college to study psychology. Before coming to Learning Works, Luquin said she didn't think much about her future. But Learning Works "gave me hope," she said. "Before I came here, I had no purpose. Now I have a purpose."

Students at Learning Works previously attended schools all over the Los Angeles metropolitan area, including schools in affluent Pasadena. One of the reasons Rahn started Learning Works was her anger at high schools for letting so many students fall through the cracks. But she's learned that traditional schools really can't give many kids in poverty what they need.

"Regular school districts don't do 24/7," she said. "Like, how would that work?"

But 24/7 is what Learning Works is all about. Chasers show up at a student's homes when they're being evicted, when their boyfriend hits them, when their cousin gets shot. Chasers also take students to doctor appointments, drive them to job interviews, bring them their school work when they're sick, all things middle-class parents do for their kids all the time. But if there's one thing almost all of the students here have in common, it's this: Their parents are not very involved in their lives. Parents might literally be missing — they're in prison, or deported, or dead. They might be working two or three jobs. Or they might not be there emotionally because of their own troubled childhoods, or addiction, or mental illness, or just the stress of poverty.

"I hate living with my mom," said Learning Works graduate Camaree Walker, wearing a T-shirt that said Education Stops Poverty. "It's nothing but just negativity when I go home. I feel self-doubt all the time."

When you don't get support at home, plus you don't always know where your next meal is coming from, you end up feeling hopeless, Walker said.

Walker graduated from Learning Works last year and was in his second semester at Pasadena Community College.

That's something Rahn initially thought all her graduates would do. When it comes to getting on a path to a middle-class life, post-secondary education is key. In the United States, 45 percent of people born into poverty remain in poverty. With a college degree, that rate plummets to 16 percent.

The declining value of a high school diploma

But Rahn said she's come to the conclusion that it may not be realistic for all of her graduates to go to college, and she's learned to measure success in other ways. She brought up the example of one of her first students, Brian, who had lots of challenges but managed to get a high school diploma.

"Someone like Brian isn't dead and isn't serving life," she said. "That was not where we were at 15 years old. I never would've thought those words would have even come out of my mouth, that he's not dead, he's not in jail. And that's great."

Does it work?

The chasers at Learning Works do an annual alumni survey. They gather in the warehouse during a school break and call all their graduates to see how they're doing, asking about jobs, government assistance, if they own cars, whether they've been in jail.

The school tallies up the responses and the data show that more than 60 percent of Learning Works graduates are working, most of them full time; 10 percent report receiving government assistance; and just 3 percent are in prison even though about a third were involved in the criminal justice system at some point while they were students.

There's no way to calculate an official graduation rate the way traditional high schools do so it's hard to know exactly how effective Learning Works is on that count. There are certainly kids who start here and don't make it. But many of those who do finish say that without Learning Works, they would never have gotten a high school diploma.

At graduation ceremonies, graduates wear caps and gowns the same purple as the chaser mobiles. Last spring there were 66 graduates, including Lugo, getting a high school diploma a few weeks shy of his 20th birthday, and Luquin, the student who figured she'd attended as many as 30 schools before ending up at Learning Works. Mendez, the student working to pay for her parent's immigration lawyer, didn't graduate but expected to in a few months. The good news for her was that her parents had come back from Mexico and she was living with them again.

Martinez graduated, too, even after she faced housing issues and boyfriend problems and then discovered she was pregnant.

"A lot of my own friends and family doubted me," she said, her voice cracking with emotion as she addressed her classmates as one of the graduation speakers. "They didn't think I could walk across this stage ever. But with the help of my nagging chaser Rob and favorite teacher Ruth, they made this day possible. You made me believe that I will graduate. Really I had no choice, you guys never left me alone," she said with a chuckle. "So as much as I complained about it, thank you."

Rahn said she's often asked if she'd be willing to open up more schools like Learning Works, but she says no, it's just not something she personally wants to do. She does think some elements of the model could be copied, including the chasers and the flexible scheduling. She pointed out that it doesn't cost more to run a school like Learning Works. It's a matter of using money differently — chasers instead of a football team, for example. Learning Works raises about $100,000 a year in outside funding to pay for things such as shoes for homeless students and even funerals for students who are killed.

Asked why growing up in poverty can make it so hard to make it through high school, chaser Carlos Cruz said when you're struggling to survive, learning algebra can seem irrelevant. "We got rent due. We got lights to pay. We got real life issues going on, than you're AX plus B equals MC. Like none of that means anything. Basic math can get you by on the streets. You just need to know how to count your money."Cruz was one of Rahn's first graduates. He said he might have been able to make it through traditional high school "if Mikala was my mom."

He thinks he might have been able to make it to a top college too, if he'd grown up with two educated parents, in a middle-class home, in a safe neighborhood. "You are a product of your environment," he said. "That statement doesn't get any realer."

An earlier version of this story referred to the mayor operating the wrecking ball in Overtown in 1966 as the mayor of Miami. He was the mayor of Miami-Dade County.

Correspondent/Producer: Emily Hanford

Editor: Catherine Winter

Web Editor: Dave Peters

Web Producer: Andy Kruse

Technical Director: Craig Thorson

Associate Producers: Ryan Katz, Suzanne Pekow

Research and Production Fellows: Lila Cherneff, Alex Baumhardt

Project Manager: Ellen Guettler

Senior Producer, Education Projects: Emily Hanford

Executive Editor and Host: Stephen Smith

Managing Director, Editor-in-Chief: Chris Worthington

Special thanks: Dylan Peers McCoy, Liz Lyon, Ruxandra Guidi, Leo Duran, the Lynn and Louis Wolfson II Florida Moving Image Archives, The Black Archives, History and Research Foundation of South Florida, Inc., and the Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce.

Support for this program comes from the Spencer Foundation, Lumina Foundation and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting's American Graduate project.

A note of disclosure: The Spencer Foundation supported some of the research that was referred to in this program. But the foundation had no influence on our coverage.

Feedback

We're interested in hearing what impact APM Reports programs have on you. Has one of our documentaries or podcasts changed how you think about an issue? Has it led you to do something, like start a conversation or try to do something new in your community? Share your impact story.